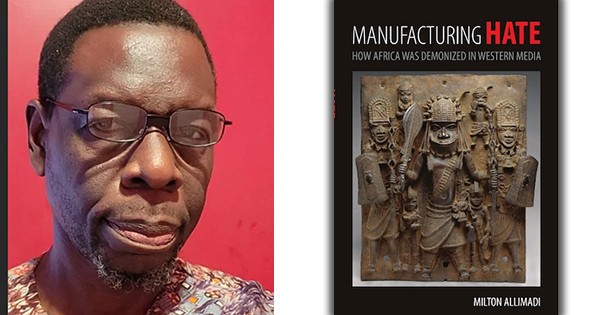

Nationwide — How did Africans, and people of African descent become so detested in the Western world? How is it that black skin color became so resented by some Europeans when in fact Africans were the first human beings in the world and all other “races” evolved from Africans? How did the concept of Black intellectual and moral inferiority relative to white people originate and evolve when the first human civilization K-met, a.k.a ancient Egypt, was African? Who were the first Western writers to create and disseminate the racist image of Africa globally and what was their agenda?A new book Manufacturing Hate: How Africa Was Demonized in Western Media (June 2021) by John Jay College and Columbia University adjunct professor Milton Allimadi, answers these and more questions. The book is available through the publisher’s website Kendall Hunt Publishing Co. at KendallHunt.com, and bulk orders can be made through Sue Saad via ssaad@kendallhunt.com or (732) 985-2244.

This is what Randall Robinson, author of The Debt, has said about the new book: “Western reporting on Africa has typically been unkind, at best. In actuality, closer to cruel. Manufacturing Hate provides the evidence.”

“This book is perfect for anyone who wants to understand how the racist image of Africa was created and disseminated around the world to justify the exploitation of Africans during slavery, during colonization and colonial rule, and for the neocolonial exploitation we see today,” said Allimadi, the author. “As a college instructor myself, I know the book is suitable for students, general readers, journalists, and anyone who wants to challenge the contemporary demonization of Africa and African descendants globally.”

Allimadi is also publisher of BlackStarNews.com and host of the podcast, The African History Club. He is an Adjunct Professor of African History at John Jay College of the City University of New York (CUNY) and of journalism at the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia.

Manufacturing Hate… takes the reader on a sweeping journey, beginning by critiquing the racist depictions of Africans in books by the arrogant European so-called “explorers,” who traveled to Africa between the 17th and the 18th centuries and gave European names to mountains, rivers, lakes, and other monuments that already had indigenous names—for example, Nam Lolwe in East Africa became Lake Victoria, and Luta Nzige became Lake Albert. These European names survive up to this day becomes “most Africans have not yet decolonized their minds,” Allimadi says.

Manufacturing Hate… shows how the early European so-called explorers were agents of imperialism. Their mission was to map out Africa for later colonial conquest and colonization by European powers—in order to exploit the continent’s resources and the labor of its people. Europe’s so-called “civilizing” mission in Africa included the extermination of 10 million Congolese during the reign of King Leopold II of Belgium, and the genocide against the Herero and Nama people in Namibia by the German colonialists.

The so-called explorers demonized Africans in order to justify exploitation by claiming that they were on a mission to “civilize” the natives.

This was absurd on its face since human beings originated in the Rift Valley of Africa and many civilizations, from Kmet, a.k.a. Egypt, to Ghana, Mali, and Songhai, flourished long before England came into existence in the 10th century. Intellectual pursuit flourished in Kmet, and Sankore University existed in Timbuktu in 900 AD, more than 700 years before Harvard was founded in 1636.

Manufacturing Hate… shows how Africans resisted colonial invasion and scored many victories against imperialism that are rarely taught in Western history classes. The legendary general Samori Toure fought the French successfully in West Africa for 15 years until he was captured in 1898. The Zulu general Ntshingwayo Khoza defeated a British imperial army led by general Lord Chemsford in 1879, killing 1,600 British soldiers.

In Sudan, the Mahdi general, Muhammad Ahmed Ibn Abdallah, defeated and killed Britain’s general Charles Gordon at the Battle of Khartoum in 1885. One of the greatest victories against European imperialism was the decisive defeat of Italy by Empress Taytu Betul and Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia at the Battle of Adwa, on March 1, 1896. The Ethiopians killed 2,918 Italian soldiers and non-commissioned officers. They also killed two generals and captured one. The Ethiopians marched nearly 3,000 Italian prisoners of war back to their capital, Addis Ababa, and put them to work cleaning the cities. Now the roles were reversed, with Africans as masters over Europeans.

Manufacturing Hate… shows how when American journalists started writing about Africa in the 20th century many adopted the racist template created by the so-called explorers to depict Africans. For example, when The New York Times sent reporter Homer Bigart to write about independence in Africa in late 1959, he filed several articles denigrating and demonizing Africans. Bigart did not conceal his racism. “I’m afraid I cannot work up any enthusiasm for the emerging republics,” Bigart wrote to Emanuel Freedman, the Times’ foreign news editor, from Ghana. “The politicians are either crooks or mystics. Dr. Nkrumah is a Henry Wallace in burnt cork…I vastly prefer the primitive bush people. After all, cannibalism may be the logical antidote to this population explosion everyone talks about.” Kwame Nkrumah, who studied in Lincoln University, an HBCU, led Ghana to independence from Britain in 1957. He invited Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the country’s independence celebrations.

The same hatred Bigart expressed for Africans in his letter was also reflected in the articles he wrote. One was published under the contemptuous headline “Barbarian Cult Feared in Nigeria” in The Times on January 31, 1960. The article read: “A pocket of barbarism still exists in eastern Nigeria, despite some success by the regional government in extending a crust of civilization over the tribe of the pagan Izi…A momentary lapse into cannibalism marked the closing days of 1959 when two men killed in a tribal clash were partly consumed by enemies in the Cross River country below Obubra.” After claiming that there had been a “lapse into cannibalism” Bigart contradicted his own concoction, when in the same article he also wrote, “None of the victims was eaten, at least not by society members. Less lurid but equally effective ways were found to dispose of them. According to the police, about twenty-six were weighted with stones and timber and thrown into flooded rivers. No trace has been found of these bodies. A few were buried in ant heaps. But most became human fertilizer for the yam crops.”

Emanuel Freedman, Bigart’s editor, encouraged the racist reporting. “This is just a note to say hello and to tell you how much your peerless prose from the badlands is continuing to give us and your public,” Freedman wrote to Bigart, in a letter dated March 4, 1960. “By now you must be American journalism’s leading expert on sorcery, witchcraft, cannibalism and all the other exotic phenomena indigenous to darkest Africa. All this and nationalism too! Where else but in The New York Times can you get all this for a nickel?”

On another occasion, when New York Times editors believed an article filed from Africa by one of its correspondents wasn’t “tribal” enough, they took matters into their own hands and inserted a fabricated incident the story, “Manufacturing Hate…” reveals. Lloyd M. Garrison, a Times reporter who covered the Biafran war of secession in Nigeria complained about the fabrication in a letter to his editors dated June 5, 1967. “The reference to ‘small pagan tribes dressed in leaves’ is slightly misleading and could, because of its startling quality, give the reader the impression there are a lot of tribes running around half-naked,” Garrison wrote complained. In other words, Garrison had never seen any “pagan tribes dressed in leaves” in Nigeria—it was concocted from thin air by New York Times editors.

In addition to affecting how Africans perceive of themselves, the historical demonization of Africa created inferiority complexes in the African diaspora as well, as Malcolm X explained in a speech shortly before his death.

Malcolm said, “…the colonial powers of Europe, having complete control over Africa, they projected the image of Africa negatively. They projected Africa always in a negative light: jungles, savages, cannibals, nothing civilized. Why then naturally it was so negative it was negative to you and me, and you and I began to hate it. We didn’t want anybody to tell us anything about Africa, much less calling us ‘Africans.’ In hating Africa and hating the Africans, we ended up hating ourselves, without even realizing it. Because you can’t hate the roots of a tree and not hate the tree. You can’t hate your origin and not end up hating yourself. You can’t hate Africa and not hate yourself. You show me one of these people over here who’s been thoroughly brainwashed who has a negative attitude towards Africa and I’ll show you one who has a negative attitude towards himself.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gb-tjIUu0i4&t=1s

“The racist image of Africa created by the so-called explorers became deep-seated in the minds of European American journalists even well into the 20th century,” Allimadi contends. “In the 1990s when I interviewed some New York Times editors and reporters, the deputy foreign news editor at the time, Michael T. Kaufman told me that when he was a correspondent in Kenya in the 1970s, he had two approaches to covering Africa, a thematic approach, and the other was what he called ‘ooga-booga journalism,’” Allimadi says. “He told me that when he was growing up, whenever Tarzan was made to speak fake African, he would say ‘ooga-booga, ooga-booga.’ Kaufman said ooga-booga reporting was the National Geographic approach to covering Africa. He said he enjoyed it and that readers did as well.”

Allimadi says there now is a new opportunity for reckoning with the legacy of demonization of Africa. Since the brutal murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, there’s been much debating of race matters and past narratives. On December 20, 2020, The Kansas City Star, issued an unprecedented apology “The Truth in Black and White: An Apology From The Kansas City Star,” for its past racist reporting on the Black citizens of Kansas City.

“Clearly there are other publications, including The New York Times, that owe an apology for the malicious demonization of Africans,” Allimadi says.

The author, Milton Allimadi, is available for speaking engagements and book readings via mallimadi@gmail.com