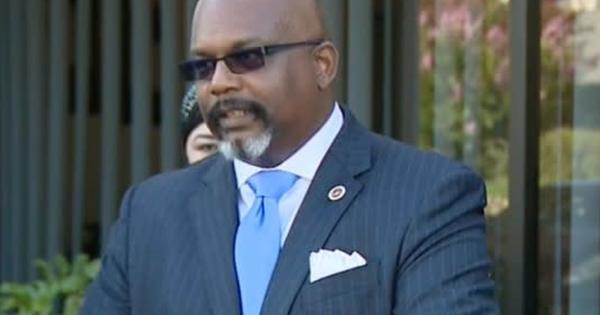

Nationwide — Attorney Zulu Ali, a former police officer and U.S. Marine Corps veteran, has released a powerful commentary titled “Attorney Zulu Ali Speaks on Justice: Trying Cases in a System Built to Oppress Black People.” In it, Ali argues that the American court system is racially biased beyond repair, compares being Black in the justice system to “playing an entire lifetime of away games,” and challenges the notion that recent reforms have meaningfully changed the system.

Full Commentary Follows:

Playing Every Game on the Road: Race, Power, and Why Our Courts Are Beyond Repair

When I walk into a courtroom as a Black man, a former police officer, and a U.S. Marine Corps veteran, I am still playing an away game.

It’s not my stadium.

Not my crowd.

Not my locker room.

And definitely not my officials.

A football coach once told me: “On the road, you can’t win by one. You’ve got to blow them out. You cannot leave it in the hands of the officials.”

Being Black in the American justice system is like playing an entire lifetime of road games. The referees wear robes, the uniforms say “District Attorney,” and the crowd is called a “jury of your peers” even when it looks nothing like your community. This is not an accident. It’s design.

Trial Is Theater – and Race Is the Script

We like to pretend trials are neutral, mechanical truth-finding processes. That’s a lie. Trial is theater. The jury is the audience. The lawyers and witnesses are the cast. The judge is the director.

And like any theater, the way the audience sees the show determines how the story ends.

In America, race is not just “a factor” in that story. It is the frame. It shapes what jurors see, what they doubt, who they believe, and who they’re willing to throw away. Studies have shown that racial bias—both explicit and implicit—infects every stage of the criminal process: policing, charging, bail, plea bargaining, sentencing, and parole. Black and Latino people are policed more, held pretrial more, and sentenced more harshly than similarly situated white people.

Black Americans are imprisoned in state prisons at nearly five times the rate of white Americans. You don’t get numbers like that from “a few bad apples.” You get them from a machine that is doing exactly what it was built to do.

The Machine Was Built for Screwdrivers, Not Justice

Imagine a factory machine designed to produce screwdrivers. One day, someone walks in and says, “From now on, we’re going to make wrenches.”

You can swap out the workers.

You can repaint the machine.

You can add inspirational posters on the wall.

But if you don’t rebuild that machine from the inside out, it’s still going to make screwdrivers. That’s what it was built to do.

Our justice system is that machine.

From slave patrols and Black Codes to convict leasing and the Jim Crow-era use of criminal courts to control Black labor, the system was built to police, control, and exploit Black bodies—and to protect white property and power. Those roots aren’t just “history.” They are baked into how police departments operate, how prosecutors charge, how judges sentence, and how juries are selected today.

Pew Research recently found that about three-quarters of Black adults say the prison system was designed to hold Black people back. Nearly nine in ten Black Americans say the courts and judicial process need major changes or need to be completely rebuilt for Black people to be treated fairly.

That’s not paranoia. That’s experience.

Jury Selection: Where “Fairness” Goes to Die

If trial is theater, jury selection is casting. And America has spent over a century making sure Black people stay out of the jury box.

Race-based discrimination in jury selection was technically outlawed nearly 150 years ago, and the Supreme Court’s Batson v. Kentucky decision in 1986 said you can’t strike jurors because of race. On paper, that sounds promising.

In reality? It’s theater again.

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) has documented a long history of courts tolerating racial discrimination in jury selection and a “continuing indifference” to fixing it. They show that people of color are consistently underrepresented in jury pools, and when they do make it into the courtroom, prosecutors strike them at far higher rates than white jurors.

Studies of specific jurisdictions have found prosecutors striking Black jurors at three to four times the rate of white jurors. EJI’s more recent work links racially biased jury selection directly to wrongful convictions and even wrongful executions.

The message is clear:

The courtroom says “Equal Justice Under Law.”

The jury box whispers “Not for you.”

What This Feels Like in Real Life

I’ve been there.

In one case, a prosecutor used a flimsy, pretextual reason to kick a Black juror off the panel. She was one of maybe two black people on the entire panel. I challenged it under the law that’s supposed to prevent racially discriminatory strikes. The court denied my motion. Everything was fine, apparently.

Later, I exercised my own peremptory challenges to excuse two white jurors for reasons that, in my view, were just as grounded as anything the prosecutor had argued. This time, the court granted Wheeler (Batson) motions against me.

Same rules. Same courtroom. Totally different energy, depending on who is being excluded and who is doing the excluding.

To add insult to injury, I was told by a district attorney that the district attorney’s office now uses that case in trainings to teach other prosecutors how to “deal with” me. Not how to deal with racism in jury selection. Not how to deal with bias. How to deal with me—a Black man, a former cop, and a Marine who refuses to bow to the machine.

If race weren’t central to how the system operates, that wouldn’t even make sense.

Why Black Jurors Matter – and Why the System Fights Them

To truly presume someone innocent in a criminal trial, a juror has to be willing to believe that:

1. The police arrested the wrong person.

2. The district attorney charged the wrong person.

3. The court allowed a case against the wrong person to go all the way to trial.

That takes a level of skepticism about the system that many white jurors simply don’t have—because the system wasn’t built to target them.

Black jurors, by contrast, often come in with lived experience: stops, searches, family members arrested or overcharged, stories of people railroaded, or simply the knowledge that the system doesn’t treat Black folks like it treats white folks or others. Surveys show that nearly nine in ten Black adults say Black people are treated less fairly by the criminal justice system than whites, compared with a much smaller majority of white adults.

That doesn’t make Black jurors “biased.” It makes them informed.

But the system treats that life experience as a problem to be solved, not a perspective to be valued. Prosecutors routinely rationalize strikes of Black jurors with coded reasons—“lives in a high crime area,” “appeared angry,” “had negative experiences with police,” “seemed too sympathetic.” EJI has documented that courts accept these explanations again and again, even when prosecutors use the vast majority of their strikes against Black jurors.

So when I say that, in many cases involving Black defendants, Black jurors are “the best jurors,” I don’t mean they’ll automatically vote not guilty. I mean they are the ones most likely to see past the costume of the system—to question the story being staged in front of them.

And that is precisely what the machine cannot tolerate.

Judges: The Referees Who Think They Are the Game

We’re told that judges are neutral “umpires” calling balls and strikes. That’s cute.

In reality, judges are embedded in the same culture and power structure as everyone else in the courthouse. Many are former prosecutors. Many worked closely with the very district attorney’s offices now appearing before them. Their professional, social, and political lives are deeply intertwined with one side of the courtroom.

Legal scholars and advocates have long noted that judges’ relationships with prosecutors, their prior roles, and their unexamined biases shape everything from who they find “credible” to how they rule on jury challenges, suppression motions, and sentencing.

I’ve seen judges who genuinely strive to be fair. I’ve also seen the other kind: Judges who treat defense objections like annoyances and prosecution objections like wisdom; Judges whose body language tells the jury exactly which side they should trust; and Judges who forget they are there to apply the law and start behaving like they are the law.

You can almost always guess who a judge was before they put on the robe: lifelong public defender or corporate lawyer? Former D.A. with a taste for “tough on crime” politics? Someone who spent their career needing respect and power they never had—and now intends to collect?

Give a person like that the power of the state, control of the courtroom, and the ability to send people to prison, and watch how quickly “judicial temperament” turns into a power trip.

As the saying goes:

Man—or woman—will always mess up power. The robe doesn’t cure that. It amplifies it.

How the System Strains Lawyers Who Insist on Trial

Defense lawyers who regularly take cases to jury trial—particularly those who refuse to simply move cases through the system—are often spread thin. As a Black defense attorney who tries more cases than most, I see this pressure up close. Because there are relatively few attorneys who insist on trying a high volume of cases, the same lawyers end up on multiple trial calendars at once. Instead of being understood as a consequence of exercising the constitutional right to trial, this reality is frequently treated as a scheduling problem attributed to the defense.

When trial dates are continued because defense counsel is actively engaged in another courtroom, that delay is often noted and quietly framed as defense “unavailability.” By contrast, when continuances result from courtroom congestion, the court’s calendar, or the prosecutor’s conflicts, those delays are typically absorbed as part of the ordinary operation of the system. The pattern is subtle but clear: when the state is not ready, it is institutional; when the defense is not available because it is actually trying cases, it is personalized.

This dynamic sends a broader message. Lawyers who insist on taking cases to trial, rather than routinely pleading them out, face structural pressure and reputational costs. In that way, the system does not only resist defendants who challenge its narrative; it also resists the defense attorneys who refuse to quietly go along with it.

The New Racial Justice Acts: Patching a Cracked Foundation

Some will point to reforms like the Racial Justice Acts and new jury selection laws and say, “See? The system is fixing itself.”

Let’s be honest about what they do—and what they don’t.

California’s Racial Justice Act and AB 3070

California’s Racial Justice Act of 2020 (AB 2542) was sold as a breakthrough. On paper, it lets defendants challenge convictions and sentences based on racial bias—whether that bias shows up in statistics about charging and sentencing or in explicit conduct by judges, lawyers, police, or jurors. We’ve already seen it used to knock out extreme gang enhancements where racist texts and data proved that young Black defendants were being overcharged. A judge tossed those enhancements under the Act, and that was celebrated as progress.

Another reform, AB 3070, was supposed to fix the long broken Batson/Wheeler system for jury selection. Instead of forcing a defendant to prove what a prosecutor was “really thinking,” it claims to use an objective test: if an “objectively reasonable” person could see race or another protected trait as a factor in a peremptory strike, the strike should not stand. That sounds good in theory. But in practice, when the same judges, with the same mindset, apply this “new” standard, the system keeps working exactly like the old one.

In my own case, the so-called reform was actually weaponized against me. A Black female prosecutor removed a Black juror for a clearly pretextual reason, and my challenge was denied. Later, when I excused two white jurors, the court eagerly granted Wheeler motions against me—using the very framework that was supposed to stop racial discrimination in jury selection to police a Black defense attorney who would not play along. The new law did not protect Black participation in the jury; it protected the old narrative and punished the person challenging it. That is not advancement—that is the same script with updated language.

These statutes are not meaningless; they came out of decades of struggle by defense lawyers, civil rights organizations, and communities who refused to stay silent. They deserve recognition. But look at what it took just to get here: more than 30 years after Batson—a decision that should have ended race-based jury strikes—California had to admit that the system was still openly discriminatory and try again. And even now, lawsuits and data show that Black and Hispanic defendants continue to receive longer sentences than similarly situated white defendants, while courts are only beginning to test how far the Racial Justice Act will really reach. We keep laying patch after patch on a foundation that was cracked from the beginning, and judges who don’t truly respect these laws ensure that, in real time, the old machine keeps doing what it was always built to do.

“Beyond Repair” Is Not Hyperbole. It’s a Diagnosis.

Some people get uncomfortable when I say the justice system is racially biased beyond repair. They hear that as hopelessness. I mean it as honesty.

If a system was designed from the ground up to do a particular thing—to control Black people, protect white wealth, and maintain hierarchy—then you don’t “reform” it into something else. You build something new.

Pew’s research shows that nearly nine in ten Black Americans believe policing, courts, and prisons need major changes or complete rebuilding. That’s not a cry for a fresh coat of paint. That’s a call to tear up the blueprints.

When you add layers of “race blind charging,” “bias trainings,” and new statutes on top of a machine designed to produce racialized outcomes, you may smooth out the roughest edges, but the product is the same Black people stopped more, charged more, jailed more, and sentenced more; Juries that don’t reflect the communities being judged; and Judges and prosecutors operating in a culture that treats Black suffering as background noise instead of a red alert sign that the system has failed.

That’s not malfunction. That’s function.

Respect Where It’s Due – and the Line I Won’t Cross

Let me be clear: I have nothing but respect for district attorneys and judges who are fair. I’ve met them. I’ve stood in front of judges who were former Marines or military veterans who didn’t need the robe to feel like somebody. Those folks tend to be more grounded. They understand chain of command, service, humility. They don’t take it personally when a defense lawyer fights for their client.

I do have a bias in favor of those public servants—especially my Marine Corps brothers and sisters—who bring that integrity into the courtroom. They exist.

But they exist inside a machine that is bigger than any one good person.

A fair judge can soften the blow in a specific case. A prosecutor with a conscience can refuse to file an unfair charge. But neither of them can turn a screwdriver factory into a wrench factory by themselves.

These are my views based on my experience as a Black defense attorney, former police officer, and U.S. Marine.

So What Do We Do?

If you’re looking for a neat resolution, you won’t get it from me. What I can offer is clarity:

1. Stop pretending race is a side issue. Race is the water the system swims in. Any conversation about “justice” that tries to tiptoe around that is just another performance;

2. Stop acting like juries are neutral. How we build jury pools, how we excuse jurors, and which life experiences we treat as “bias” is where racism shows its face most clearly;

3. Stop romanticizing judges as neutral referees. Look at who they were before the robe, whose company they keep, whose worldview they share—and how often their “discretion” cuts only one way; and

4. Stop talking about reform like a tune-up. When Black Americans overwhelmingly say the courts need to be rebuilt, believe them.

And if you’re Black and find yourself in this system—whether as a defendant, a lawyer, or a potential juror—understand this: you are not crazy, you are not “too radical,” and you are definitely not alone.

You are playing an away game. The crowd isn’t cheering for you. The officials are not neutral. The scoreboard is rigged. So yes, we fight like hell inside the existing system—file motions under the Racial Justice Act, make the record, challenge biased jury strikes, expose racist patterns. That’s survival. But we cannot mistake survival tactics for structural change.

Until we rebuild the machine itself, it will keep doing exactly what it was built to do. And for Black people in America, that means one thing:

The justice system isn’t broken.

It’s working.

That’s the problem.

Attorney Zulu Ali is the Founder and CEO of the largest Black-owned law firm in Southern California’s Inland Empire. Learn more at ZuluAliLaw.com